Take, for example, the Garfield comic strip: it was in a lot of papers, but there was really nothing to it. Yet they have sold millions of stuffed Garfields, and they even made a movie out of a lousy three-panel comic strip that was about about a cat that eats lasagna. Strips like Bloom County and Dilbert were higher quality and were frequently about something, but they also went the merchandising route, cashing in on plush Opuses and Dogberts. The Simpsons is a merchandising monolith.

In such a world it's hard to imagine someone who would turn down all that cold hard cash to maintain artistic integrity. Yet there is such a man. He and his creation are the topic of a documentary called Dear Mr. Watterson. The director was recently interviewed on NPR.

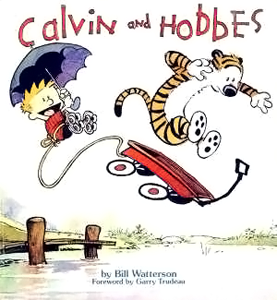

The comic strip Calvin and Hobbes, written and drawn by Bill Watterson, was a classic. It's about Calvin, a boy who thinks his stuffed tiger, Hobbes, is real. Calvin is constantly ambushed by Hobbes, and Calvin talks about this imaginary playmate as if he's a real tiger. His friends think he's nuts, but he has amazing adventures with dinosaurs and spaceships and film noir detectives, even though the world around him is disappointingly mundane.

People still love Calvin and Hobbes: it was smart, funny, philosophical, touching, poignant and sometimes mean and crude. It ran for 10 years, and when Watterson had said everything he wanted to say, he stopped writing the strip. That was almost 20 years ago. In a world where pointless comics like Mark Trail and Rex Morgan, M.D., soldier on for decades, penned by faceless corporate shills, Watterson voluntarily ended one of the best comic strips ever written.

Bill Watterson never sold out, even though the strip has the most obvious merchandising gimmick you can imagine. One of the titular characters is a stuffed animal. But you can't get an officially licensed Hobbes stuffed tiger.

It's not like Watterson is a pauper and needs to sell out: Calvin and Hobbes was tremendously successful during its run, and book-length collections of the strips are still doing a brisk business. The strip is syndicated in reruns and you can see it on the web. So Watterson has no financial need to sell out: he's got a steady income and has maintained the artistic integrity of his creation.

But that doesn't stop the vast majority of successful artists and writers from cashing in. Most, given the opportunity, decide to merchandise their creations even though they're already doing quite well.

Now, I'm not saying that selling out is always a bad thing. But most Americans seem to take it as an article of faith that more is better, as so eloquently stated in the immortal words of The Tick, spoken to his disciples in the Mystic Order of Arachnid Vigilance (from The Tick #9, "Road Trip", 1991):

Always ... always remember: Less is less. More is more. More is better, and twice as much is good too... Not enough is bad, and too much is never enough except when it's just about right.This attitude, which almost caused the collapse of our entire economic system in 2008, was presaged in the pages of The Tick. To finance their organization the M.O.A.V. planned to "buy real estate for no-money down and sell it at huge profits!" The author was a seer!

The Tick is a satirical superhero comic created by Ben Edlund, who has "sold out" several times with licensed merchandise and animated and live-action television versions of The Tick. He's also done a lot of work in Hollywood (well, mostly Canada) on shows such as Firefly, Angel, Supernatural and Revolution.

So, yeah, he's a sellout. But if Edlund had never sold out I wouldn't have found the original black and white Tick comics. The shows he's worked on, and the specific episodes and characters he's created are self-aware, self-critical and self-deprecating. They never take themselves too seriously.

It warms my heart that Bill Watterson can keep the memory of Calvin and Hobbes pristine (at least until his money-grubbing heirs get their mitts on it). But I also like that Edlund went on to do a lot of new and entertaining work that was made possible by him selling out.

The most important thing is these men got to choose: they had control over their creations and could choose whether to license them. This is unlike many artists and writers who've been shafted by giant corporations, like Siegel and Shuster of Superman fame.

If there's anything that should be changed in our intellectual property laws it's the idea that the creator of a work of art can sign away the rights to their creations. It should be illegal, like selling your own children.

To decide whether something is a sell-out or not, you have to ask whether the merchandising is a betrayal of the original artistic concept. Star Wars action figures? Not a sellout. Superman Halloween costume? Not a sellout. Tick live-action TV series? A lousy failure, but not a sellout.

But the core of Calvin and Hobbes is that Calvin's antics and the living, breathing Hobbes are products of his vivid imagination. Calvin can take any mundane object and through the power of his mind transform it into a grand adventure.

A licensed Hobbes stuffed tiger that replaces a child's imagination with a product manufactured by people whose childhood dreams ended in a sweatshop making slave wages? Definitely a sellout.

2 comments:

The most important thing is these men got to choose: they had control over their creations and could choose whether to license them.

Yet other people shouldn't get to choose, right? There are so many things we should never be allowed to choose - for our own good. Yet here you can celebrate two choices that run directly opposite one another.

Why is choice only good some of the time?

And those people making "slave wages"? They're lined up by thousands ready to make any money at all to escape the rice paddies and sugar cane fields. But back to the fields with them! We can't let mere peasants take the first steps to escape rural poverty! Not until completely unskilled (outside of agriculture) people are able to move directly into First World middle-class housing making "living wages" for the most menial job, and good wages for anything better. Of course, then the cost of labor goes much higher, and there's no point moving manufacturing there. So it's just better they stay in the paddies and know their place. Wouldn't want anyone selling out, now would we?

Post a Comment